Interaction and reaction

October 23, 2025

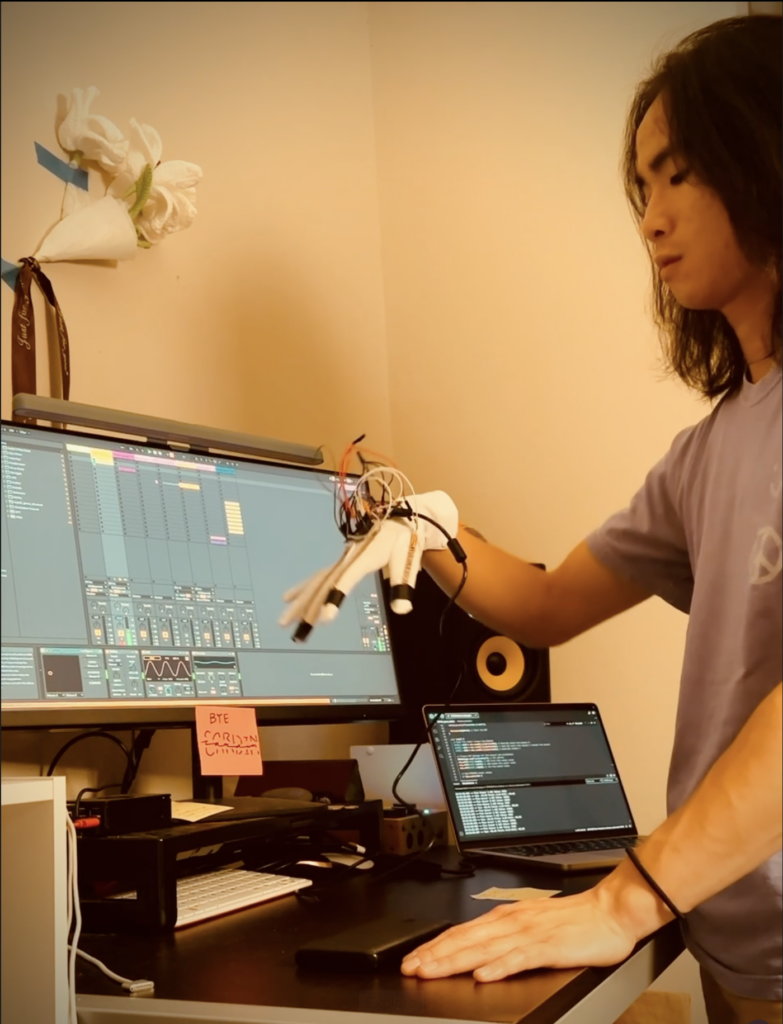

Through wearable technology, Cardin Chung ’26 is creating a conversation between dancer, sensor, and audience in real time.

By Jana F. Brown

Wearable technology, explains Cardin Chung ’26, amplifies subtlety and nuance during live performances. It’s a fine line the USC Kaufman School student is walking — well, dancing — as he experiments with how simple movements, including the smallest changes in hand position or orientation, can create dramatic shifts in a performance.

In explaining a piece of original choreography, for which he also created background visuals and composed music, Chung talks about the engineering side of the sensor-laden glove he wears on his right hand, noting that the mitt is controlling both the visuals and the sound.

“Whenever I closed my hand, the music muffled a bit, and you heard these voices coming in throughout the space,” Chung recalls. “Different pictures of people appeared, or the visuals were warping based on the movement of my glove. As a dancer, it was interesting because I wasn’t always sure what would pop out, so it became this live response.”

Does this mean Chung is creating an original piece each time he performs with the smart glove? Yes and no. Depending on how much movement emanates from the gloved hand, there can be greater variation from one performance to the next. Those instances turn into real-time research for Chung as he graces the stage. But variation all depends on how much freedom of control the glove hand is afforded.

“There have been cases where the majority of it ends up being not pre-choreographed or pre-composed in terms of the structure and how I want to approach it,” Chung says. “It really depends, but the cool part is I have that flexibility to do so.”

His research is all part of Chung’s senior capstone at USC Kaufman, where he’s majoring in dance, while also pursuing minors in jazz piano and web development and a specialization in cybersecurity.

“It has been a pleasure to witness Cardin’s exploration of dance and wearable technologies,” Dean Julia Ritter says. “His research exemplifies the kind of interdisciplinary innovation possible at a school of dance like Kaufman when embedded within a research institution.”

Chung can track his new obsession back to a music technology course with Professor Tom Hall, who first taught him methods for programming audio effects and manipulating sound. During one of those lessons, Hall introduced Chung to an Arduino, a microcomputer that can be programmed and connected to sensors for data processing. While it has many applications, after learning about the Arduino’s capabilities in robotics, Chung had a breakthrough.

“I thought, ‘What if we use Arduinos for dance and use the same sensors that robotics uses,’” Chung recalls, “‘but instead of tracking robotic movement, we track dancer movement?’”

That question turned from idea into practice when Chung accepted a residency in the Dance Research and Residency Center at Lake Studios Berlin in summer 2024. The opportunity gave him the chance to develop wearable technologies for dance capable of controlling live music and visuals.

Although he identifies as a “STEM kid,” Chung is largely self-taught in the electrical engineering skills required for connecting dance with technology. He’s spent loads of time reading books and watching videos to understand how to build circuits and manipulate hardware. Despite having a coding background, the hardware side was completely new to him, but he’s driven by the potential of what the technology could become. Chung explains the basics of how it all works: body orientation and speed of movement affect the audio and visual elements of performance, while distance sensors respond to spatial positioning. The sensors also detect movement, such as the opening or closing of a hand, the data gets processed by the microcomputer Chung built, and those signals instantly control the volume and tone of the music, plus the lighting and appearance of the images projected on a background screen. While adding tech represents only a subtle distinction for the audience, viewers might notice muffled music when Chung closes his hand or, when he moves it closer or farther away from his body, that different visual elements appear on the screen.

Unlike pre-recorded performances, this creates a live feedback loop, Chung explains, as the dancer responds to what the technology produces, which then responds to the dancer’s movement. In other words, as Chung responds to the sounds and visuals his movements create, that response influences his subsequent movements, creating a conversation between dancer, technology, and audience in real time.

During the residency in Germany, Chung was charged with creating a 10-minute performance with a tight deadline. He admits that was a struggle because “I was trying so hard to make the technology cool and make the music make sense.” That overthinking made it challenging for Chung to actually dance. That was true until late one night, when he was casually playing around with the sensor and had a realization.

“I was thinking too hard about all of this,” Chung recalls. “The centerpiece of this entire thing is the fact that I’m the body in this, there’s this interaction happening with me and this glove.”

This year at USC, Chung is working with multiple dancers, each donning sensors, to explore how the introduction of this active technology affects the way dancers approach improvisation and composition. “What new forms of awareness and creativity arise,” he asks, “when a dancer receives real-time sensory responses to movement?” Chung plans to move away from wearing multiple hats (choreographer, composer technologist) as he creates to find greater collaboration with other artists.

“It’s more fun when it’s collaborative,” he explains, noting that working with other dancers has quickened the pace of what he understands about the technology and its capabilities.

Beyond his graduation from USC, Chung’s mission is to make his research accessible as open-source assets. He’s also passionate about creating installation work and immersive experiences that go beyond traditional dance performances, using technology that tracks movement, pressure, and positioning to create truly sensory experiences.

His ultimate vision, however, is to make technology more available while keeping the dancer and artistic meaning at the center, rather than featuring the spectacle of the technology itself. While the innovation carries infinite possibility, Chung still sees dance as the essential glue that gives meaning to creative innovation. At the end of the day, his goal is to create meaningful work.

“The dancing gives bodily context, conceptual context, and visual context for [this technology] to exist in a space,” he says. “But the one who makes it all make sense is the dancer.”

All photos courtesy of Chung.