Faculty Q&A with Anindo Marshall

September 27, 2016

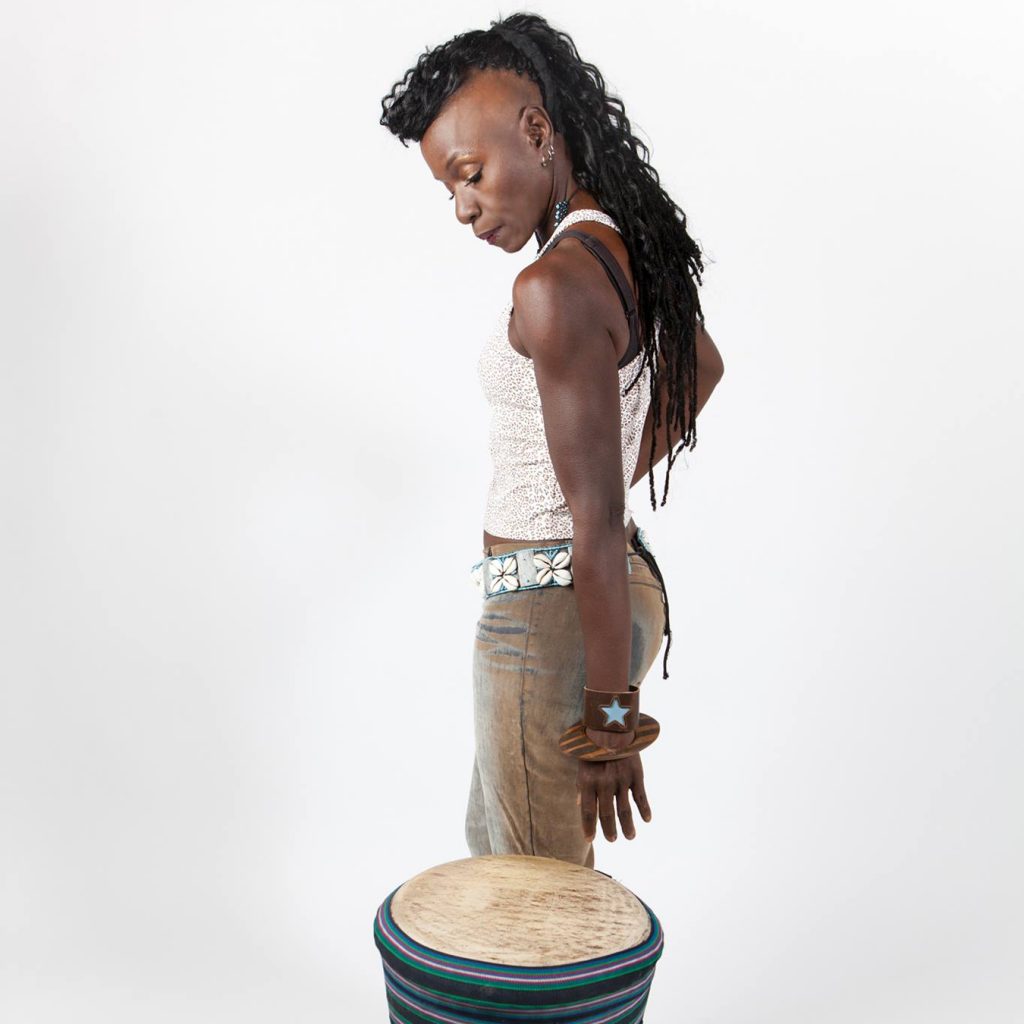

USC Kaufman faculty member Anindo Marshall | Photo by Isabel Avila

Faculty member Anindo Marshall joined USC Kaufman this fall to teach Afro-Cuban dance. Marshall, who owns 100 or so drums from all over the world, is proud to carry on the Dunham Technique legacy, a method of teaching created by the late Katherine Dunham, known as “the queen mother of black dance.” In her career as a musician, dancer and educator, Marshall has experienced stardom in home country of Kenya, recorded music in Europe and used her art to help incarcerated youth in Los Angeles.

What drove you to music and singing?

I was born and raised in Kenya, which became independent from Britain in the 60s, when I started going to school. At first the school was all for white kids and, after the independence, was integrated with indigenous, African and European students.

When I was about 8 years old, I was going home after school and looked into a hall. There were little girls in an auditorium dressed in pink and wearing beautiful tiaras. I thought, “My goodness. What is that?” I kept going there every day to take a peek and I told my dad that I wanted to do that beautiful thing. He went to my school and asked the teacher, “What’s my daughter talking about?” She said, “Oh! It’s Ballet!” The program had an extra cost, so I couldn’t join right away. I was heartbroken.

When I went to high school, I was able to join the performing arts program and I studied opera, ballet and organ. One day an American dancer visited our school and told me to go to her class. I got a first glance of the Dunham Technique there, which was a completely new thing for me.

How did you become a Dunham Technique ambassador?

It took a while from the moment I was in high school until the moment I dived into the Dunham Technique. At the end of my last year, I got a recording contract that made me become famous in Kenya, playing drums and singing. Years later, I went to Europe to sign a contract with EMI records.

However, for all those years, I was constantly looking for this dance that the African-American lady had taught me back in high school, and I couldn’t find it anywhere. It had all the elements I liked: ballet technique and modern features, but also drums and movements that were familiar to me.

After four years recording in Europe, I fell the need to create my own music, which is mix of African with R&B and pop, but the record label didn’t go for it because it didn’t fit their business plan. I decided to continue as an indie artist.

One day, I got an invitation to the United Nations convention in New York dedicated to Kenya. To accompany my performance, they hired the legendary percussion artist Babatunde Olatunji. He invited me to an African festival in Brooklyn and I learned about a class in NYC on a type of drums that were new to me. I visited that class and, lo and behold, the professor starts doing warmup exercises with the movements that I had been searching for for years. I asked, “What is this?” They said, “Dunham Technique.” I said, “I want to study this. Who can teach me?” They said, “Katherine Dunham!”

I immediately changed my visa and came back to the U.S. to work and learn the technique, that’s how I met Ronnie Marshall, my future husband and Dunham Technique master.

I worked with Ms. Dunham until 2006, the year she passed. She had told me she wanted me to continue her legacy of teaching her technique and I did so. I have traveled all over the world teaching the Dunham Technique and collaborating with universities. I’ve been keeping the legacy alive for more than 20 years.

How does the African style complement the traditional western styles?

In the Dunham Technique, you need to have ballet training and get your body placement correct. But you also need to master cultural styles that help you bring ballet down to earth. The Dunham Technique brings the best of both of these worlds.

Back in the day, if I had wanted to become a ballet dancer, I wouldn’t have been able to make it. I didn’t have the body or the skin color. Things are now changing, but it was the Dunham Technique that allowed me to become a fulfilled dancer.

Traditionally, ballet has been a very Caucasian dance form. The Dunham Technique brought diversity in the form of movement. When Ms. Dunham started, in the time of segregation, she could only work with black dancers because it was forbidden for black dancers to share the stage or train next to white dancers. But she was interested in Russian ballet, so she learned by sneaking into classes. Eventually, she was able to create her own movement, involving dancers from multiple backgrounds. The Dunham Technique really integrates culture and brings all kinds of dancers together.

What are the takeaways that you want students to learn from your class?

In my Afro-Cuban course, we go beyond dancing and discuss culture and traditions. When you’re talking about Afro-Cuban, you cannot separate dance from culture. Ms. Dunham had to go to the Caribbean islands to perform dance anthropology studies that would help her master the style.

When the vast amount of slaves came from the Congo and parts of West Africa to Cuba, the Catholic and the African traditions got mixed and symbols incorporated from one culture to the other. I teach my students to recognize the different sides of Africa and not to generalize all into one big package. I also urge them to cultivate a sensibility that helps them understand the history and culture of a big portion of the Americas.

Which projects are you currently working on?

I work as an educator with different organizations. I teach at LACHSA (Los Angeles County High School for the Arts), from which many USC Kaufman students graduated, and I maintain relationships with various universities. I also created Adaawe, an all-female percussion and vocals band, which represents the artistic identity that I had looked for when I became an independent artist.

With Dream A World Education, I work with 5-year olds, teaching simple life values like kindness, friendship and gratitude. By involving parents and teaching social emotional skills through music, dance, theater and visual arts, we contribute to raising happy and confident children. The program in Los Angeles has been so successful that the city is asking us to expand it very rapidly.

Finally, I work with teenagers who have been through hardship. My partners and I used to visit juvenile jails voluntarily and introduce the kids to drum therapy to help them let out their troubles. Some of them stopped involving in crime after the therapy. The results of our work with them caught the sheriff’s attention and, after five years of volunteering, the project began to receive public funds.