The brown ballerina (still) exists: Lenai Wilkerson’s senior project

April 25, 2019

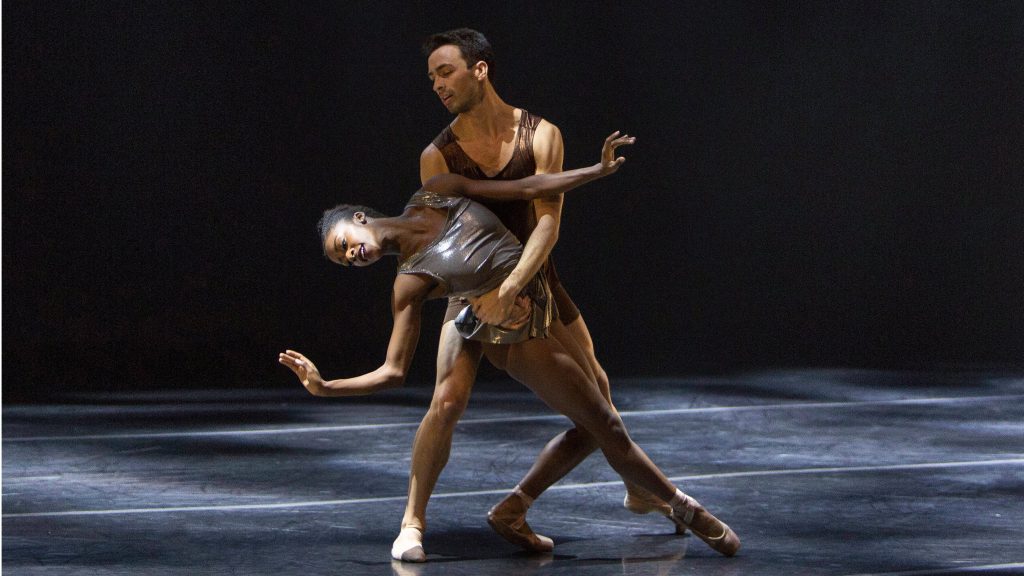

Lenai Wilkerson and Juan Miguel Posada (BFA '19) in Jodie Gates' "On the Double" | Photo by Rose Eichenbaum

Lenai Wilkerson (BFA ’19) was told at age 12 that she would not become a professional dancer. She was serious about ballet and had already decided it was her future career, but her dance teacher suggested basketball or track instead. Her passion, the teacher said, would not be enough. Wilkerson pushed on despite the criticism. Upon graduation, she will join New York company Ballet Hispánico as an apprentice, pointe shoes and all. But facing this adversity has added another layer to her career goals.

“I realized at a very young age that I might actually be an activist in this respect. My purpose was to be a voice for so many other brown ballerinas that would come after me,” she said. “I would have to say something about brown body politics and how they function in the ballet scene.”

A few years later, she encountered a new teacher, Oscar Hawkins. Hawkins, a black male from Maryland, danced with the Kirov Ballet Company II, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal, and more during his career. He told her to throw racist comments out the window. Eventually, she attended Baltimore School of the Arts (though a three-hour round-trip commute did not make it easy), where she studied ballet daily.

“I put in so much work, because I wasn’t going to let someone tell me I couldn’t fulfill the dreams I had for myself,” she said.

During her studies, she had the same conversation many more times. Her physique, teachers said, wasn’t “right.” Rather than give in, she spent more hours in the studio. Years of training in diverse techniques led her to the USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance.

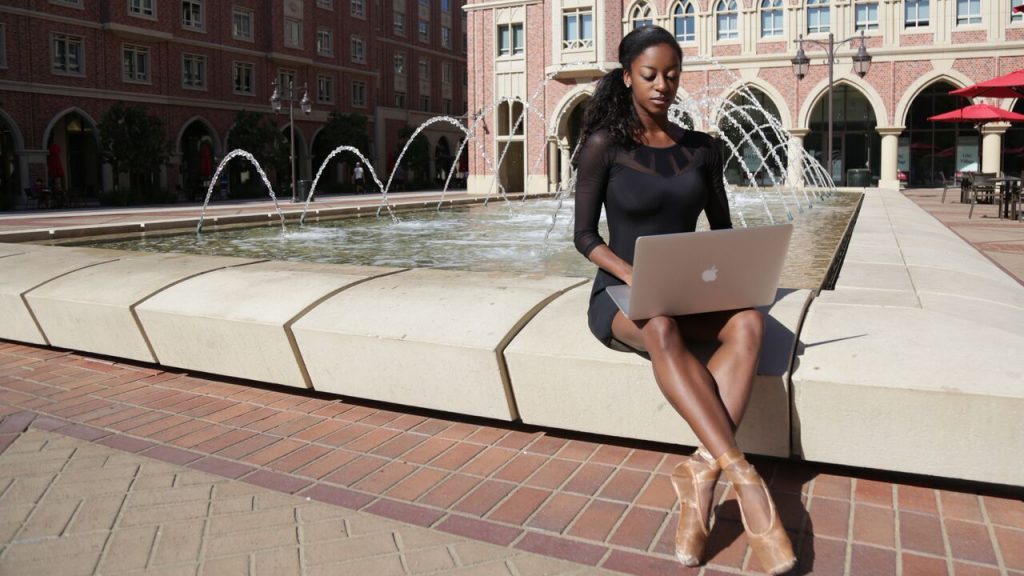

Lenai Wilkerson (BFA ’19) studying at USC | Photo by Mary Mallaney

Translating the experience: a scholarly thesis

Here, as an artist scholar, Wilkerson’s courses informed her knowledge of invisibilized black and brown ballerinas. These were generations of black women whose stage presence had been erased in the white retelling of dance history. A course called Dance in Popular Culture with faculty member Saleemah E. Knight introduced her to dance scholar Brenda Dixon-Gottschild.

Gottschild’s definitive text on invisibilization, titled “The Black Dancing Body,” moved Wilkerson to look further into the subject. Her own experiences in a black body made these stories, this research, all too relevant. At first, she focused on it in her dance courses; eventually it percolated through all of her studies. As a political science minor, Wilkerson found she could use her educated voice to change her own story.

“I became infatuated with this coined phrase: ‘the brown ballerina exists,’” Wilkerson said. “Every paper I wrote, I used the opportunity to relate to a different aspect of Gottschild’s thesis, and to explore and expand my own.”

During her senior year, Wilkerson took private units of coursework as directed research. During these hours, she compiled a miniature thesis—twenty pages of her own findings on the brown ballerina. The goal: to publish her work as a reviewed scholarly paper.

Once the time came to propose her senior project, Wilkerson already had a presentation in mind.

Activism aspirations

She decided that her fifteen-minute TED Talk-style presentation would give an abbreviated overview of her research.

“I thought, ‘what better way to bring this voice to the limelight than explaining my research?’ Everything here has informed the dancer that I am and the activist that I wish to be, and I have so many viewpoints from which to share,” she said.

The discourse won’t end at USC Kaufman. Though she’s off to Ballet Hispánico a few days after commencement, Wilkerson will continue her research for a lifetime. The first step is to connect with Gottschild directly. Though it may seem difficult, a few USC Kaufman faculty members have studied under Gottschild herself.

“I know it’s important to have the conversation with her before I approach publication, between the perspectives from our own generations, before we can talk about where the climate is going,” she said.

Once she has opened that door, she hopes that her published research will open the discussion and advance the conversation around the brown ballerina. In a field that is 60 years behind, she says, there must be progress. She wishes to become an artistic or executive director one day, and shift the focus herself so that the invisibilization epidemic no longer plagues ballet. With a long career dreamed ahead of her, she just might convince her field: the brown ballerina (still) exists.

By Celine Kiner